Why most AI gets news wrong

The problem is not intelligence, but perspective

Most AI tools that analyse or summarise news are not wrong because they are unintelligent. They are wrong because of the criteria and cultural perspectives they are built on.

AI systems do not observe the world directly. They learn from data, rules, and decisions made by people. Those people live somewhere, work within certain systems, and carry their own assumptions. In practice, this often means that many AI models reflect a predominantly American, centre-left worldview. That influence is not always obvious, but it is consistent.

This matters because the United States also has strong political, economic, and corporate interests. What is emphasised, softened, or ignored in public narratives often shows up again in AI-generated interpretations of the news.

Analysis is not the same as interpretation

Many tools are good at summarising what an article says. Some go a step further and label coverage as left, right, or neutral. Tools like this can be useful, but they stop short of interpretation.

They show positions. They do not explain meaning.

What is often missing is an answer to a more important question: what does this actually imply for people, and what is not being said? I wrote about that gap in How to analyse the news without pretending to be objective.

That gap between analysis and interpretation is where most AI gets news wrong. It reproduces the surface of an article without interrogating its structure, scale, or intent.

Cultural bias hides inside criteria

Bias in AI does not only come from data. It also comes from criteria.

A clear example can be found outside journalism. In the Netherlands, AI systems were once used to identify potential welfare fraud. Certain criteria were treated as neutral signals, such as living with extended family or having irregular housing situations. In practice, these indicators disproportionately flagged people from migrant backgrounds.

The system was not malicious. It was culturally narrow.

The same mechanism applies to news analysis. When criteria are shaped by one cultural norm, behaviours that fall outside that norm are more easily labelled as suspicious, extreme, or irrelevant.

Scale is where narratives quietly break

One of the most common failures in AI-driven news analysis is scale.

Some topics receive intense attention even when their real-world prevalence is limited. Others remain underreported despite affecting millions of people.

Terrorism is a clear example. In many Western countries, attacks are rare, yet fear remains high. Long-term global data shows fluctuations rather than a continuous rise, and in several regions incidents have declined. At the same time, violence in places like Somalia has increased significantly, while receiving relatively little sustained coverage.

AI systems trained on Western media inherit this imbalance. They amplify what is visible, not what is proportionate.

A broader global view makes this clearer. Long-term datasets show that terrorist incidents have declined in many parts of the world, while increases are concentrated in a small number of regions, such as Somalia. World maps and timelines make this imbalance visible in a way single headlines never do.

Emotional framing distorts judgement

Another recurring pattern is emotional framing.

News stories often centre on individual victims with names, faces, and personal histories. This creates empathy, but it also distorts scale. Larger groups become statistics, and context fades into the background.

This is a classic dehumanisation pattern. A few lives are rendered vivid, while millions are reduced to numbers. Once that happens, extreme responses can feel justified, even when they are disproportionate.

AI tends to reproduce this framing faithfully. It mirrors the emotional emphasis of the source without questioning its effect.

Missing perspectives are rarely flagged

Many articles present strong claims without including all relevant voices. The person being accused is absent. Legal representatives are quoted briefly or not at all. Judges or independent experts appear only at the end, if they appear at all.

AI summaries usually follow the same order and emphasis. If crucial information is buried, it remains buried.

This is not misinformation in the strict sense. It is structural incompleteness.

Four structural checks that matter

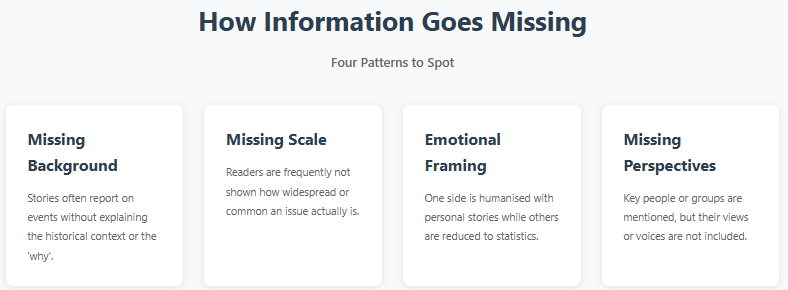

When analysing news, four structural elements are especially important:

Background. Does the article explain historical or situational context, or only the event itself?

Scale. Is the issue widespread, exceptional, or statistically marginal?

Emotional framing. Are emotions used to guide interpretation, and are groups treated asymmetrically?

Missing perspectives. Who is not quoted, and whose interests are not represented?

Most AI tools do not evaluate these elements explicitly. They focus on coherence, tone, and frequency instead.

Speed creates confidence without care

There is also a structural incentive problem. People expect answers quickly. AI systems are rewarded for speed and fluency, not restraint.

A confident answer delivered in seconds feels authoritative, even when it lacks depth. Few tools are designed to slow readers down or introduce doubt in a constructive way.

What AI should do differently

AI does not need to become neutral. Neutrality is not achievable.

What it needs is structural honesty. Clear signals about uncertainty. Explicit separation between description and interpretation. And frameworks that expose gaps instead of filling them automatically.

Collaboration across cultures and data sources would help. So would more openness about training assumptions and limitations.

Using AI without surrendering judgement

This is not an argument against using AI to read the news. It is an argument for using it differently.

AI can surface patterns that humans miss. It can handle volume that no person can process. But it should support judgement, not replace it.

That is the approach behind Impact News Lens. It does not tell readers what to believe. It highlights structure, omissions, and framing so people can decide for themselves.

The goal is not to distrust everything. It is to recognise that confidence is not the same as accuracy.

If AI is going to help people understand the world, it has to start by admitting where it cannot.